NICE Cybersecurity Training

Welcome to the second Trustwai newsletter! In this issue, we are going to try and tackle a small aspect of a much broader topic, and hopefully do so without falling down any rabbit holes. Training is a large topic space, with branches into various areas of our modern society. This includes discussions around theory of mind, distributed cognition, teamwork, and, ultimately, what it means "to be competent" at something. To further this, the viewpoints on the topic are many. From those involved in the AI space to those in education (child or adult), there are many lenses upon which we can look at the broad concept of training. In order to anchor our discussion here a bit, we are going to focus our newsletter on the viewpoint of the organization and look at cybersecurity training of the workforce.

It is likely self-evident to many that training is a requirement for any well-functioning organization. One doesn't need to search far to come across the cliché meme of a CEO talking to a CFO in which the CEO is petitioning to spend money on training, and the CFO is refusing. "What if we don't train them and they stay" is the closing line, which seals the deal to the finance person that this spending is a requirement. For whatever reason, which we won't discuss here, this doesn't ever seem to translate into the real business world.

News

Fear, uncertainty, doubt (FUD) is a common technique used when trying to sell anything cybersecurity. You don't have to search far to find a cybersecurity report that lists human error as one of the key methods attackers exploit when breaching organizations. At time of writing, on the main page of the Verizon DBIR, it lists that "68% of breaches involved a non-malicious human element, like a person falling victim to a social engineering attack or making an error". Don't think too hard about these numbers however, otherwise you'll end up asking yourself many questions of relevance that don't make it to the mainstream. The narrative that "our users are the weakest link" is disingenuous, if not lazy, yet pervasive in the cybersecurity industry.

Governments have been taking different angles to talk about cybersecurity training. For example, the 2023 Biden-Harris National Cybersecurity Strategy Implementation Plan includes objectives to strengthen the cybersecurity workforce. Governments seem to be stopping just short of mandating training within legislation, leaving it up to industry practices and other regulatory/compliance mechanisms to fill the gap. Building a little bit on our first newsletter, sometimes a lack of defined goals in legislation can leave us with a false sense of security. Most training programs mandate/stipulate/define only awareness training, leaving out other aspects that are critical for a well-functioning organization.

There has been a push in recent months to start to track cybersecurity more effectively at the board level within companies. This is likely a result of government action in this space, along with the generally increased scrutiny of upper levels of management. We here at Trustwai believe that security is an emergent property of an organization, and context setting, which is done at the highest levels of management, is crucial in setting the context which makes security possible. No longer should responsibility for security failures stop at the CSO (Chief Scapegoat Officer). The National Cyber Security Center in the UK has published a Cyber Security Toolkit for Boards which is a good read overall. The toolkit has various areas of which training factors into key indicators of cybersecurity success.

Paper Overview

The central source for this newsletter is a product of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and their publication of the NICE Framework. NICE stands for the National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education, for those wondering. We will also include the Canadian version of this, The Canadian cyber security skills framework, which is effectively an attempt to apply NICE to the Canadian market.

You can think of the relation between these two documents like this. The NIST NICE builds a foundation for defining cybersecurity skills in terms of tasks, knowledge, and skill statements. They then group these statements based on work-role definitions. NIST assumes large, US entities (whether enterprises or government/military) and breaks the work-roles down in that context. This is great but can be hard to apply to the vast array of "real businesses" that exist in the marketplace. The Canadian take is about leveraging the great work done and applying it appropriately to small/medium business. They define adjacent work-roles, for example, respecting the fact that organizations likely distribute security concerns among existing work-roles rather than hire specifically for cybersecurity.

Levels of cybersecurity training

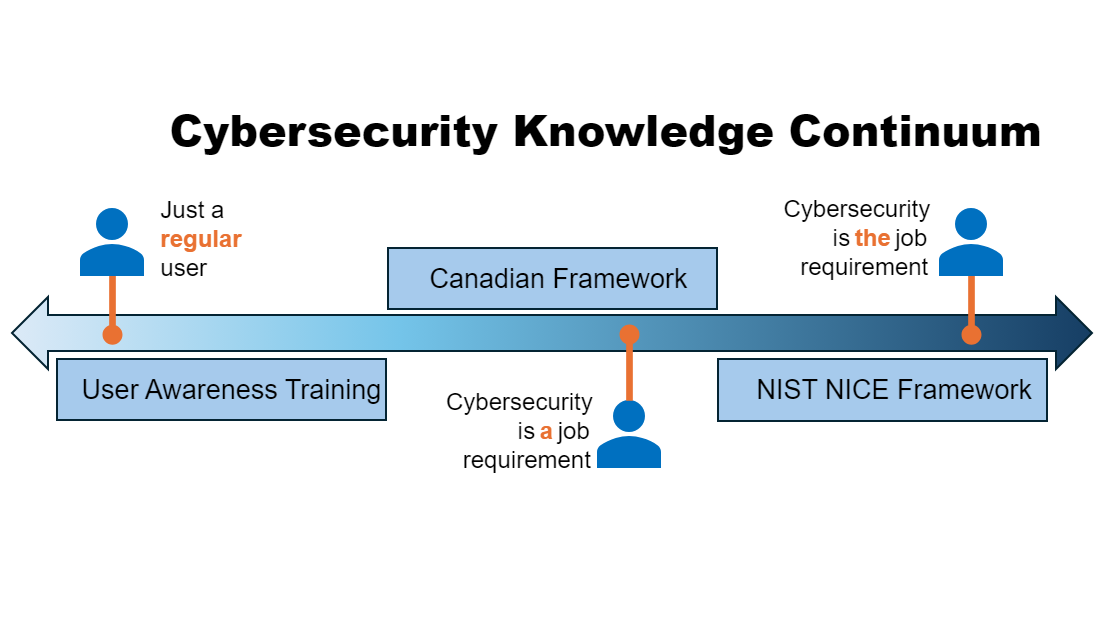

I've made a simple continuum to help showcase how these frameworks could fit together.

Starting on the left-hand side, you start with just regular users. These are just organizational users who perform a variety of job functions. Once you get into the center area, you now have job functions that are primarily one thing (for example, operating a power generation plant) but has a set of cybersecurity requirements laid out either via organizational policy or via regulation. The last area is more for cybersecurity professionals, and the various job functions they may do within an organization.

So, the way to look at it is this. The NIST NICE framework is great as a foundation way of defining cybersecurity training objectives but is primarily geared for work-roles where cybersecurity is the primary function. The Canadian Framework attempts to take this guidance and make it more generally applicable across organizations that need to distribute the accountability of security among other team members. Lastly, general user awareness training is not really covered within either of these two frameworks, but you likely could extend the "process" here to that domain should you wish.

We would argue that in an organization, there should be no "regular users" where user awareness training is enough for them to meet their organizational obligations. All work-roles should require some form of role-based training.

Tasks, Knowledge, and Skills

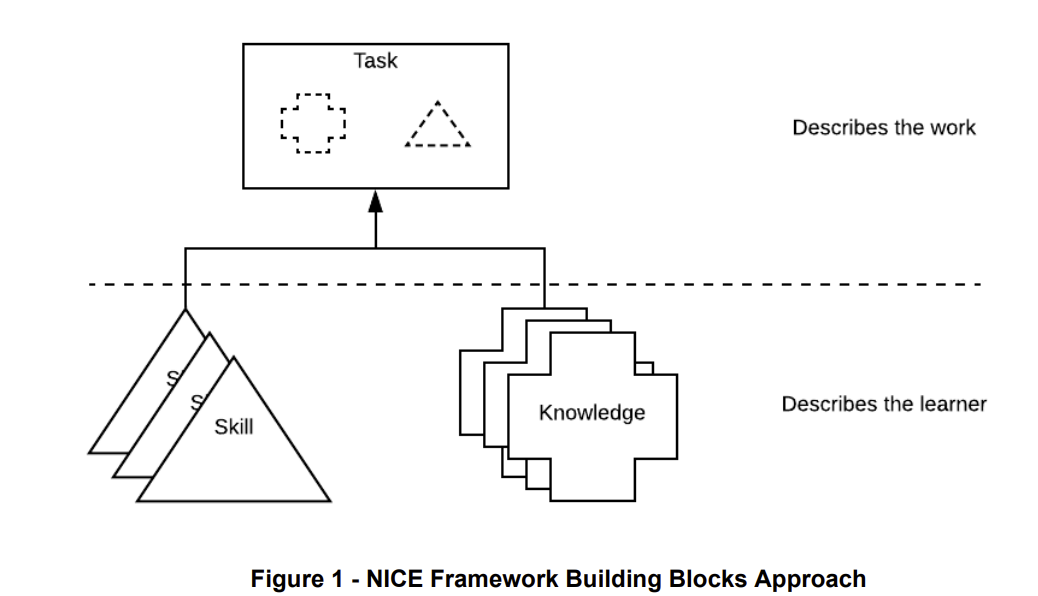

The above diagram is taken directly from the body of the NIST NICE document. The whole framework is about defining the cybersecurity tasks one would do, and then describing the knowledge and skills that someone would need to perform that task. These tasks can then be grouped together either via work-roles or via competency areas. The idea is that you would do different groupings depending on your perspective and viewpoint. So, if I was hiring, I would care about competency areas. If I was doing organizational design, I might care more about work-roles.

Tasks, which describe the work, can be "defined as an activity that is directed toward the achievement of organizational objectives, including business objectives, technology objectives, or mission objectives". They go on to advise that task statements should be straightforward and must not contain the organizational objective within the statement. This is to allow for different groupings.

Some examples of task statements from the companion excel:

- Identify gaps in security architecture

- Perform security reviews

- Define baseline system security requirements

- Configure network hubs, routers, and switches

As you can see, there are a lot of ways to define task statements that can cover a broad range types of activities you would want someone to perform.

Tasks and then related to knowledge and skill statements. Again, from the document,

- "Knowledge statements relate to task statements in that only with the understanding described by the knowledge statement will the learner be able to complete the task".

- "A learner who is not able to demonstrate the described skill would not be able to complete the task that relies on that skill"

Okay cool. Let's dive a bit deeper.

Information vs Knowledge

What does it mean to know something? Let's take an example knowledge statement.

- Knowledge of data classification standards and best practices

- Knowledge of data classification tools and techniques

When I say I have the knowledge in the previous statements, do I mean ability to replicate or memorize? Do I mean an understanding of core concepts to the level that I can apply? Do I mean context-free understanding of data classification, or context specific? Is knowledge from 10 years ago acceptable?

To me, the knowledge statements provided in the companion excel are more information statements than they are knowledge. I believe that knowledge means more than just being able to regurgitate information on demand. Knowledge is only useful if I can actually apply it in my context and situation.

An interesting observation is that many work-roles defined within the standard make use of the same knowledge statement. So, a work role such as cybersecurity architect might have the knowledge statements defined above, and a work role such as systems administrator may also have it. Clearly, there is a degree of difference that these two roles need to be familiar with the knowledge domains, but that isn't quite reflected in the framework.

Skills and ASHEN

I found the skills statements to also be a bit interesting in how they are being used to describe the learner. Let's take an example of:

- Skill in evaluating security designs

Against what? I mean this seems like quite the broad skill. In some cases, I may want someone who is capable of taking quick looks at systems, evaluating them against his/her intuition of what is most important given the context. In other cases, I may want someone who is super rigorous and diligent in this area, mapping risk all the way down to technical controls and then evaluating their effectiveness.

ASHEN is a knowledge management framework created by Dave Snowden over at the Cynefin Co. I really like this knowledge management framework, and it brings in a couple of other aspects that we might want when we are looking at skills. For example, we may want to also define the Experience that the person has. Experience in a startup vs experience in a large organization is quite a bit different. I'm not saying you can't move between but understand the experience someone has might help you understand better how they will fit in with your particular needs.

One that might be easily overlooked is the idea of ‘natural talent’. We may want someone who is flexible, able to get to that 80-90% mark quickly, in certain situations. In other situations, we may want someone who needs to follow the top-down approach, making sure all boxes are checked. Flexibility isn't always good, and this is where ethics and responsibility may play a part.

An Example

Let's take a quick example to see how we might be able to use these frameworks. Let's assume that we are kicking off a project to introduce a new technology into our organization. Maybe, to get a bit more specific, we are looking at a new data platform tool to enable citizen developers.

Step 1: Define/Identify Roles

In step 1, let's have a look at which roles are applicable for our scope. We want to include project members, operations members, and maybe, if we are progressive enough, the end users/administrators who will ultimately use the platform. For this, we can use the excel to try and grab the roles we want.

| Role | Description |

|---|---|

| Program Management | Responsible for leading, coordinating, and the overall success of a defined program. Includes communicating about the program and ensuring alignment with agency or organizational priorities. |

| Secure Project Management | Responsible for overseeing and directly managing technology projects. Ensures cybersecurity is built into projects to protect the organization’s critical infrastructure and assets, reduce risk, and meet organizational goals. Tracks and communicates project status and demonstrates project value to the organization. |

| Technology Program Auditing | Responsible for conducting evaluations of technology programs or their individual components to determine compliance with published standards. |

| Cybersecurity Architecture | Responsible for ensuring that security requirements are adequately addressed in all aspects of enterprise architecture, including reference models, segment and solution architectures, and the resulting systems that protect and support organizational mission and business processes. |

| Secure Systems Development | Responsible for the secure design, development, and testing of systems and the evaluation of system security throughout the systems development life cycle. |

| Database Administrator | Responsible for administering databases and data management systems that allow for the secure storage, query, protection, and utilization of data. |

| Systems Administration | Responsible for setting up and maintaining a system or specific components of a system in adherence with organizational security policies and procedures. Includes hardware and software installation, configuration, and updates; user account management; backup and recovery management; and security control implementation. |

That is probably a good enough list for this example. The first callout I'd likely make is that the role descriptions are based on the ones in the companion excel. As the framework is extensible, you are free to create your own. Secondly, bringing in that Canadian viewpoint, not all of these roles might map to specific and different "people". In an agile methodology, you could likely have one person playing multiple of these roles. In some cases, some responsibilities might be pushed off to the vendor, which will likely change how you interact with it. Lastly, since we are introducing a platform, I've omitted the Secure Software Development role as it might be distributed outside the project scope at your organization.

Step 2: Define Knowledge, Skills, Task Statements

In this step, we can use the companion excel to look at the predefined knowledge, skills, and tasks statements for each of the roles identified above. We can then select a subset of those that we want to include as part of our project. For example (We'll only look at a couple):

| Role | Task Knowledge Skill Statements |

|---|---|

| Program Management | - Knowledge of risk management processes - Knowledge of cybersecurity policies and procedures - Knowledge of cloud computing principles and practices - Knowledge of cybersecurity requirements - Skill in determining supplier trustworthiness - Skill in applying standards - Determine operational and safety impacts of cybersecurity lapses - Develop/maintain strategic plans - Develop independent cybersecurity audit processes for application software, network, and systems |

| Cybersecurity Architect | - Knowledge of encryption algorithms - Knowledge of cybersecurity policies and procedures - Knowledge of business operations standards and practices - Knowledge of database systems and software - Knowledge of business continuity and disaster recovery policies and procedures - Knowledge of new and emerging technologies - Knowledge of identity and access management principles and practices - Skill in designing security controls - Develop cybersecurity designs for systems and networks with multilevel security requirements - Develop cybersecurity designs for systems and networks that require processing of multiple data classification levels |

Don't get hung up on the accuracy of the above, I'm just doing this as an example. As you can see, the knowledge/skill/tasks statements are wide ranging. Even in the ones I selected, you may ask, "how much of this is necessary for this project to be successful"?

Step 3: Plan training

Once you've broken out the statements, you can start to plan how you would go about doing training. In some cases, this might be organization or role-based training that you would institute in a training program. In other cases, this might form the requirements for hiring and/or staffing of this particular project. Lastly, using the agile approach, this might prompt a day of training for the particular sprint where team members brush up on context-specific security aspects before going to implement. The point is that the framework offers no real guidance here, and you need to take an approach that is right for your context.

Conclusion

As we wrap up, it is hard not to think that maybe this whole newsletter sheds more light on our view of education as the single best investment one can make, whether personally or as an organization. Again, we should combat the narrative that users are the weakest link and look to turn them into our greatest asset. Simply mandating awareness training is a short-sighted approach that barely scratches the surface of the complexities of the modern threat landscape. This has left many organizations vulnerable, as they fail to address the need for in-depth, continuous skills development and a deeper cybersecurity culture.

The NIST NICE framework, with its comprehensive focus on developing cybersecurity roles and workforce capabilities, is tailored towards larger entities, often overlooking the unique challenges faced by smaller entities. It provides a robust structure for identifying and developing cybersecurity talent, but its application can feel out of reach for organizations without dedicated cybersecurity resources. On the other hand, the Canadian Cyber Security Skills Framework offers a more accessible model for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). It prioritizes practical, role-based skill-building, acknowledging that SMEs have different resource constraints and risk profiles.

Both of these frameworks have their strengths and hopefully you are now curious what role-basked cybersecurity skill-building could look like for the organizations you participate in. Only by integrating these frameworks with suitable and practical, organization-wide initiatives can we hope to transcend the limitations of current cybersecurity awareness training paradigms and truly enhance cybersecurity resilience at all levels.

Member discussion